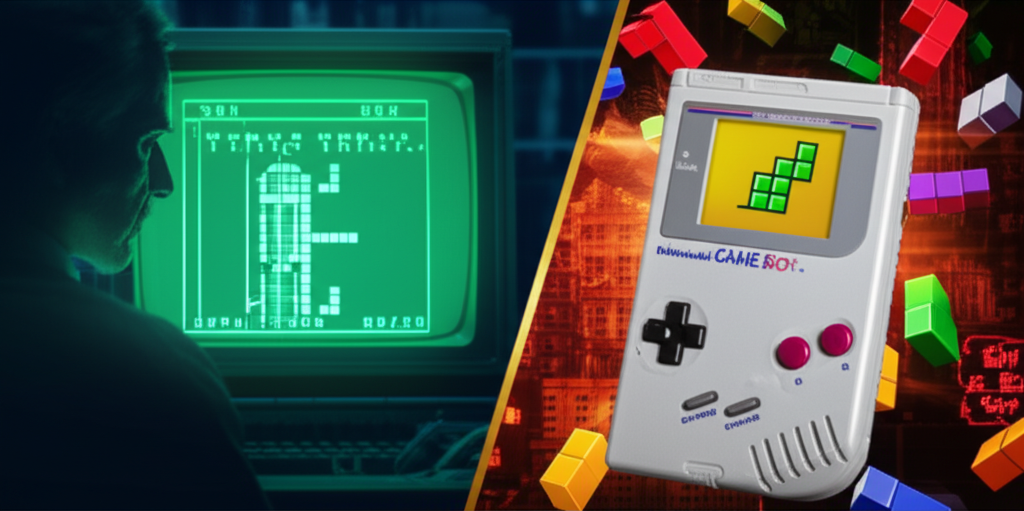

From a Moscow Lab to the Game Boy: The Unlikely Journey of Tetris

Created by a Soviet scientist in 1984, Tetris was a simple experiment that was never meant to leave the lab. Its journey across the Iron Curtain ignited a complex intellectual property battle, a story of Cold War intrigue that culminated in its iconic pairing with the Nintendo Game Boy.

Few digital experiences are as universal as Tetris. The familiar geometric shapes, the simple goal of clearing lines, the instantly recognizable theme music—it's a game that transcends age, language, and culture. Yet, for a game that defined portable entertainment for a generation, its origins are rooted not in the corporate labs of Japan or Silicon Valley, but within the stark, utilitarian walls of a Soviet research center during the height of the Cold War.

A Puzzle Born in Moscow

In 1984, Alexey Pajitnov, a computer scientist at the Dorodnitsyn Computing Centre of the Soviet Academy of Sciences in Moscow, was tasked with testing the capabilities of a new computer, the Electronika 60. To do so, he decided to create a simple program based on a childhood puzzle game he loved called pentominoes, where players arrange twelve unique shapes, each formed from five squares, into a box. Pajitnov simplified the concept, using four-square pieces—tetrominoes—and had them fall from the top of the screen. He christened his creation "Tetris," a portmanteau of "tetra" (the Greek prefix for four) and "tennis," his favorite sport.

The game he created was immediately and profoundly addictive. Colleagues at the Academy couldn't stop playing, and productivity reportedly dipped as the puzzle spread from one computer to another. However, under the Soviet system, the concept of private intellectual property was nonexistent. Pajitnov's creation belonged to the state. He received no bonus for his work, only his regular salary. The rights to Tetris were held by the Soviet government, a fact that would soon become the central point of a convoluted global battle.

An Unofficial Export

Tetris was a ghost in the machine, a piece of software spreading organically. It was ported to the more popular IBM PC and began circulating on floppy disks throughout the Eastern Bloc. Its reputation grew, eventually crossing the Iron Curtain into Hungary, where it was spotted by Robert Stein, a software salesman for the British company Andromeda. Stein was mesmerized and immediately saw its commercial potential. Believing he had secured the rights from the original programmers via a faxed telex, he began licensing the game to Western developers, including Mirrorsoft in the UK and its American affiliate, Spectrum HoloByte. The game was a hit on home computers, but Stein had made a critical miscalculation: he didn't actually have the rights. The Soviet state, through a newly formed organization called Elektronorgtechnica (ELORG), was the sole entity that could legally license Tetris.

The Tangled Web of Western Rights

What followed was a story so complex that many have described it in near-mythic terms. As one commenter notes, the scramble for ownership was far from a simple business deal.

The story of how Nintendo got the rights to this game is pretty much a spy thriller.

By the late 1980s, multiple companies believed they owned a piece of Tetris. Mirrorsoft had sold sub-licenses to Atari for the Japanese arcade and home console markets. Nintendo, meanwhile, was preparing to launch its revolutionary handheld device, the Game Boy, and was seeking the perfect game to bundle with it. Henk Rogers, a Dutch-born game publisher based in Japan, had secured the Japanese rights for Nintendo's home console, the Famicom, and was convinced Tetris was the killer app for the Game Boy. The problem was, no one seemed entirely sure who held the all-important handheld rights. Everyone assumed they were part of the broader "computer" or "console" rights, a common misconception that would soon unravel spectacularly.

The Game Boy Connection

Determined to secure the rights for Nintendo, Henk Rogers flew to Moscow in 1989, unannounced, to negotiate directly with ELORG. In a series of tense, high-stakes meetings, Rogers discovered the shocking truth: neither Stein, Andromeda, Mirrorsoft, nor Atari had ever been granted console or handheld rights. The Soviet officials at ELORG were furious to learn that companies were selling versions of their state-owned property without permission. Rogers, presenting himself as an honest broker, was able to build a rapport with Pajitnov and the ELORG officials. He successfully negotiated a landmark deal, securing the exclusive handheld rights for Nintendo. Simultaneously, representatives from Mirrorsoft and Atari were also in Moscow, trying to legitimize their own claims, leading to a dramatic confrontation that saw Rogers emerge victorious on behalf of Nintendo.

Global Domination and a Creator's Reward

The pairing of Tetris and the Game Boy was a masterstroke. The game's simple, short-burst gameplay was perfectly suited for a portable device. It turned the Game Boy from a promising piece of tech into a cultural phenomenon, selling over 35 million units bundled with the game. For many, the idea that Tetris wasn't a Japanese creation was a surprise.

I thought it was from Japan too... for the longest time.

While the world fell in love with his game, Alexey Pajitnov saw no financial benefit for years. The royalties flowed to the Soviet state. It wasn't until 1996, after emigrating to the United States and after the original state-owned copyright expired, that he and Henk Rogers were able to form The Tetris Company. Finally, the creator of one of the world's most beloved games began to receive the royalties he was due. The story of Tetris is more than the history of a video game; it's a tale of creativity under constraint, Cold War business intrigue, and the undeniable power of a perfectly designed puzzle.

in

in